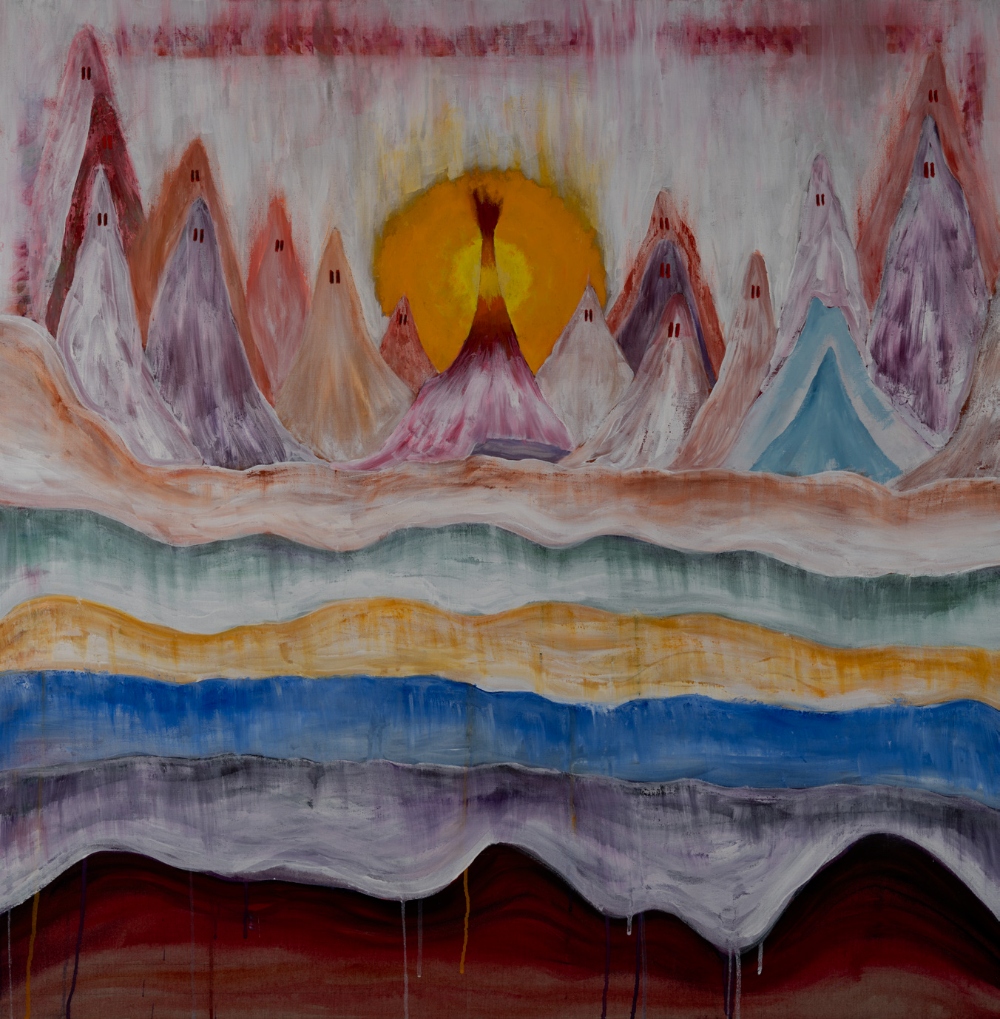

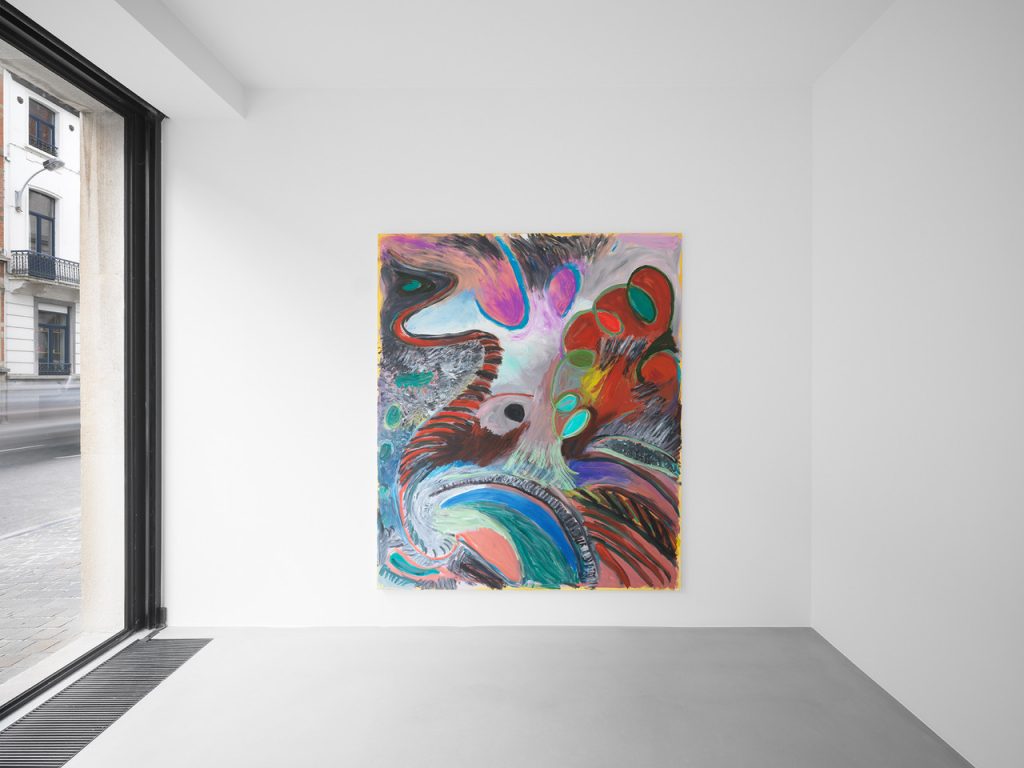

Interview: Artist Josh Smith On His Process and The Large-Scale Abstractions in “Keyhole”

Understanding the artist’s latest work from his Bushwick studio to Xavier Hufkens gallery in Brussels

Recently on view at Xavier Hufkens gallery in Brussels, Josh Smith’s Keyhole comprised a new collection of large-scale, colorful abstract paintings and figurative monotypes. One of the best-known contemporary painters of his generation, Smith has walked the line of representational art, text-based painting and abstraction. The artist divides his time between New York and Tennessee, and has a massive studio in NYC’s Bushwick, where he spoke with us about painting, sculpture, keyholes and being uncomfortable in the studio.

Can you talk about how you arrived at this new body of work in Keyhole?

The last body of work that I made were cityscapes. I do things one way… that is good and the other way that is fun. I start to see in one painting something that works and then I can apply it to another painting—it’s a system of checks and balances, but also requiring individuality. Part of painting is the struggle to stop; knowing when to stop. I’ve been trying to take out the busy energy of these more recent paintings. There are moments when I’m working and I feel like that. The abstract works are just me. In the other works there is an image, so it is a collaboration between the image and me trying to keep myself out of the equation. And at the same time, I don’t want the image to become a picture. These are me, marks made with tools that I have, how I feel and what I want to see or don’t want to see.

What was the transition like going from representation to abstraction?

What happened naturally is that everything melted. The reapers, the fish, the name paintings, all these shapes and my style that has developed, I basically unwound everything and let it settle into a morass of colors and the feel of the other paintings. It’s a comfortable place to fall and it makes a lot of logical sense. I’m trying to bring it to a place where I can let it settle and then rebuild it.

I don’t want to work because I know what I’m doing, I want to work because I want to learn and discover things that I hadn’t considered

I’m still the one who is making the paintings—same paint, same brushes, just different forms. To step back into that abstract mindset feels really good and like the type of challenge I need at this point in my life. It’s very satisfying to paint representationally and that’s not why I work in New York, or participate in this way. I don’t want to work because I know what I’m doing, I want to work because I want to learn and discover things that I hadn’t considered. I have to go through [various stages on the canvas] to find what I want, not what I need… I feel like it’s my responsibility to not be comfortable in the studio.

What is your experience like working in the studio?

Working in the studio is a challenge. Sometimes I think, this looks good and this looks bad enough to keep. But then I’ll come back the next day and feel it looks really busy. Everyone will say, “Don’t touch them” and that’s when I know I have to do it. When somebody else says it’s done all I can say is, “If you are in the studio and you understand them and are going to come to the opening, don’t you want to be surprised?” It’s all collegial and fun, it’s not passive aggressive shenanigans.

Looking at several of the paintings at Xavier Hufkens, it seems like viewers eyes land on certain spots or on certain shapes as a way to enter into the painting.

That’s why I called the show Keyhole. I thought that as well. I looked up the definition of keyhole and it was a hole and a lock into which a key is inserted. I just love that image, it’s so clinical and worked both ways, also as something that can be looked through. It is romantic and is also practical and, in this case, I guess we are the key.

What was it like making work during the last two years?

Most of my work deals with context and, well, the pandemic—I didn’t want to present a dark show. I don’t feel like it’s appropriate. If I’m in New York and don’t go outside much, it [emotions] can get darker and darker and darker. That can have value, and that’s why people love New York art, because it reflects the human condition. I’m not depressed much lately, thanks to cycling.

What is your painting process like? Do you start with a solid colored ground?

I’m trying to make the worse thing possible. My initial abstract paintings made in 2007/6 were evidence of what I decided abstract painting was: dots, squiggly lines, blocks of color, triangles—all the things that I love. I have a ton of brushes and make different shapes or fill areas with color. I layered these shapes and gestures to make abstract paintings and it worked.

Now, I’m trying to be a pro-thinking, pro-developer and take the cynicism out of that idea and apply it to my recent work. Every time you go out to race, you’re not going to win. With painting, there’s nothing at stake except my own sense of earning the privilege to continue learning like this. You might like it so much that you hate it because it defeats your preconceived notions of what Modernism is.

Images courtesy of Josh Smith and Xavier Hufkens Gallery