Interview: Antionette Carroll, TED Fellow and Founder of Creative Reaction Lab

Guidance on design, equity, community and being OK with failure

St. Louis-based Creative Reaction Lab (CRL) actively works with communities, specifically their youth, to devise plans aimed at overcoming systemic disadvantages—from racial and economic inequities to social and cultural limitations and policy that disproportionately separates minorities in the education and housing sectors. Through CRL’s programming, young people interested in entrepreneurship, creativity, community development and design learn how their interests can make changes in their community and help in the fight for justice. CRL’s founder, president and CEO, Antionette Carroll, approaches design as a tool—more problem-solving than poster-making. She wants to address the plights of African-American and Latinx communities by activating youth and instilling a sense of understanding for leadership and upward-reaching design.

We met with Carroll after her TED Talk earlier this year to discuss her “equity design” practice and understand how it can be a force of change in and for communities.

We’re going to start with a basic but also complex question. What does design mean to you?

Design to me means power, and it means transformation. There are some times when I tell people that design was the invisible disruptor before “disruption” was the buzzword of the time. As an industry, we like to relegate it down to just the things that are tangible or that we feel that we actively or intentionally work around. Design is not just the tables that we see, something we can physically touch, or the clothes we’re wearing. It’s everything around us and how we engage with each other.

We talk about innovation like it’s this invisible cloud of greatness, but when you think about the concept of design, it literally is the creation of things that are new and refashioned things that are old. We need to replace the word “innovation” with the word “design” and acknowledge the role its playing in society.

Has that always been the definition of design for you? Or is that part of this new chapter of your life and work—where you’re thinking about design and equity?

It’s definitely part of a new chapter. For me, design originally was graphic design… We were taught in school that design was book covers, logos, the thumbnails you hate doing because they wanted you to do 100 of the same thing. It wasn’t until I gained more professional experience and started to work in more diverse and inclusive spaces as a designer that I started to see how massive it was.

Part of it is my own personal journey—exploring what design can be and what design is—but I’m also doing the same thing in the space of equity. When I talk about equity design, it’s something I’m personally also going through and supporting others that are going through that process as well.

As you are on this path of design thinking and teaching design—teaching people to be equity designers, are there tools from your earlier perception/practice of design that you’re applying? You’ve said that in graphic design class, you were taught about things that were very technical, and it wasn’t necessarily about strategy or innovation or lateral thinking. But now you’re helping people understand how they are an element in a world and that they can influence that world around them.

That’s also why I took business and social science classes, to supplement that. You see this in the arts and you see this in design. Many times we get stuck on the technical aspect and not really seeing the conceptual things and how much power we have in the space—so it was always one of those journeys.

As time went on in my college education, I went more in the communication, social sciences, sociology, anthropology route and started to see the emergence and overlap in that and say, entrepreneurs. What I found is that, many times, it’s a language game. In many cases, we do similar things. We just might have a difference in technicality or awareness. But people talk about design thinking, I sometimes laugh and say, “Get in front of people that branded it” because when I was in school there was no “We’re gonna teach you design thinking.” That’s not how that was.

We’d be able to accomplish more by acknowledging there are actually a lot of similarities in design that overlap with other things

When I see people that are, unfortunately, just going through the process and saying “I’m just going to check off the boxes” (such as “ideating” which is brainstorming or gang-storming; or “prototyping” which is experimentation or developing a minimally viable product) I see that we’ve also intentionally put up labels and separations to try and make ourselves the experts. We’d be able to accomplish more by acknowledging there are actually a lot of similarities in design that overlap with other things.

Your current work isn’t about the way a lot of us think of traditional design. It’s really systems design in many ways, or community design. How are you taking your graphic design skills or traditional “design skills” or trade skills and applying them to a different solution?

I do want to get to the term “re-designers” because I think that’s a key term. Because it’s similar to the fact that my organization’s name is Creative Reaction Lab—as opposed to being proactive. It’s because we understand the reality is that we’re always reacting to something, because everything has been built. We’re not in a world where we’re starting from scratch, and I think what tends to happen is most people think of design, or the world around us, as a blank sheet of paper. They say, “OK, this is literally nothing, I’m going to create something.” But, they’re not really acknowledging that we are bringing in our previous experiences that we have and bringing our biases. We’re bringing environmental influences into the creation of this.

It’s the same when I think about redesigning. Yes, we can say we’re designing, but it comes from this mindset that we’re always creating something new, whereas when we’re redesigning. It’s acknowledging that there’s been things historically here that we have to be conscious of before we actually go in and try to do design-based work.

With the Creative Reaction Lab, you’re not doing what a lot of people think of as traditional design projects. How are you taking your education and experience as a more “traditional” designer and applying that to community, activist or equity design?

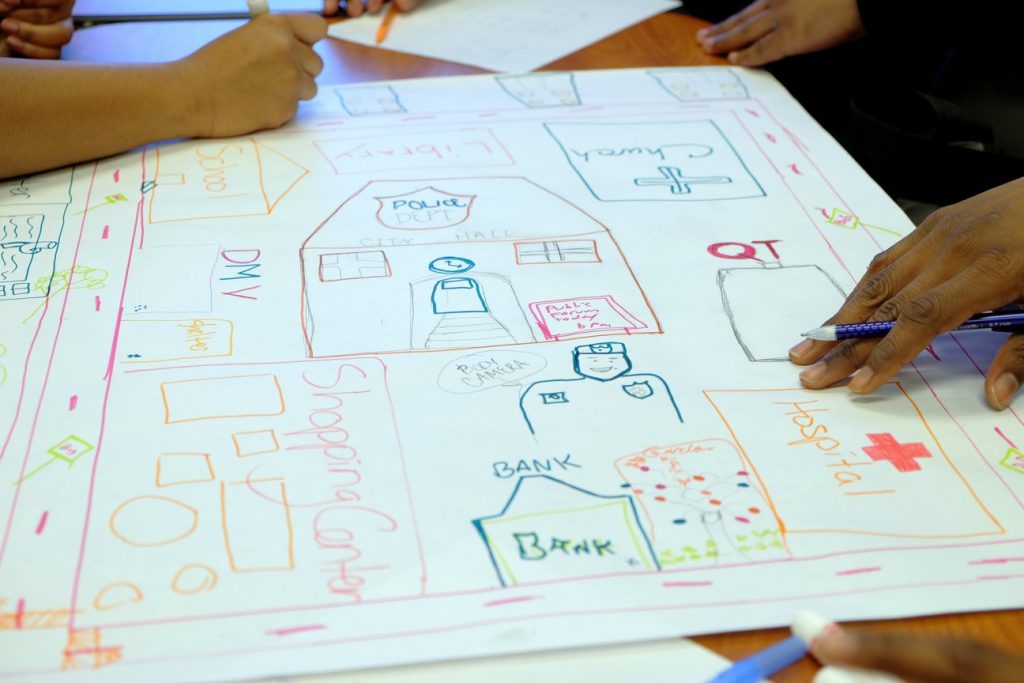

It’s interesting, because I still sometimes go back to my traditional design mindset. Even when our youth come up with ideas, I very much still have that critique and critical moment that we’d have in design class where we we’re doing thumbnails. It’s the same, except we’re having them go through it in a more intangible way—perhaps not “intangible” because they still are sketching, still bringing in visual learning and visual understanding.

I think a lot of it has been interwoven into the work we’re doing so much so that I don’t even know if I can outright pull it and say this was 100% graphic design. What’s interesting is when I’ve met with people or people look at what we’re doing and say, “Oh, well I wouldn’t think to visually explain it this way,” that’s because, as opposed to us just talking, we’ll sketch it out or create a graphic. So, there’s still traditional graphic design elements in our work, it’s just not this consultation model that you tend to see in design firms—that is unless you see the community (or society at large) as our client. I guess you could view it that way—that we’re a group of designers addressing client problems and what’s happening in society. But, as far as I know, the client is not paying us.

The ability to present your work and this idea of failure (which was engrained very early in design school and even as designers) and our natural tendency to be vulnerable—it’s because, as an industry, we have to.

Our critics are everywhere and, as an industry, we’ve learned to have tough skin. We still have to have tough skin. We have people who think racism doesn’t exist. We have people who think not everyone deserves certain rights. So part of it is taking the ability to absorb feedback—to realize what pieces I should take and when I should use my imagination or my creative confidence and understanding to address the problem.

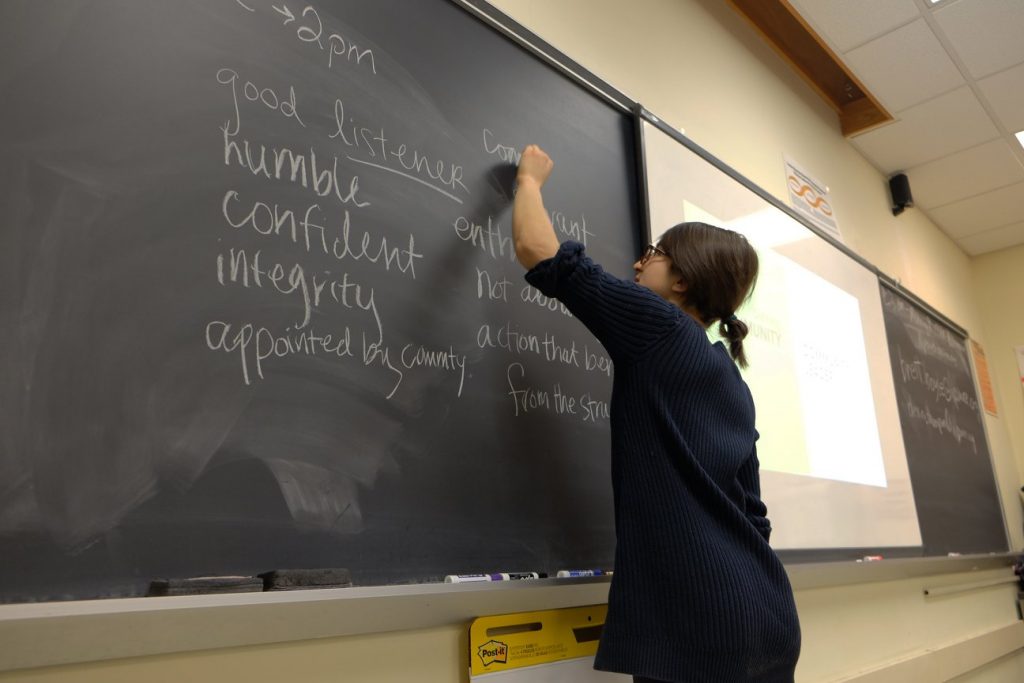

For people who come through the Lab, what’s the most valuable thing you can give them or teach them?

When we work with youth, it’s interesting. We just finished a cohort of our community design apprenticeship program and one of those students/apprentices at the end said, “One of the greatest things we appreciate you doing is that you asked questions and allowed us to dissect and understand them ourselves.” And that’s something we’ve engrained in our process and I will argue is a design process in itself.

Sometimes it’s hard when dealing with people that haven’t had the ability to work that way. Or, we sometimes partner with institutions and they’re like, “Well, what’s going to be the final product?” And we don’t know. We haven’t gone through the process yet.

Mistakes will be a part of everything you do, and you’ll be OK with it. Failure will be a part of you, and you’ll be OK with that.

We’ve tried to train our youth that that’s not a reality of society and it shouldn’t be. If you already know what your solution is going to be before you understand the problem, is it really the correct solution? So that’s something we really try to instill in them—understanding when people say that it’s a process or it’s a journey, it actually is. Mistakes will be a part of everything you do, and you’ll be OK with it. Failure will be a part of you, and you’ll be OK with that. But then it’s also understanding the role itself, which is where that equity piece really comes in, in whatever issue we’re trying to address. You’re not just bringing your professional self to the table, you’re also bringing your personal self—so we very much engrain that into our youth.

Images courtesy of Antionette Carroll/Creative Reaction Lab