Cxffeeblack’s Mission to Decolonize the Coffee Industry

An all-Black supply chain helps to reclaim the real history behind coffee

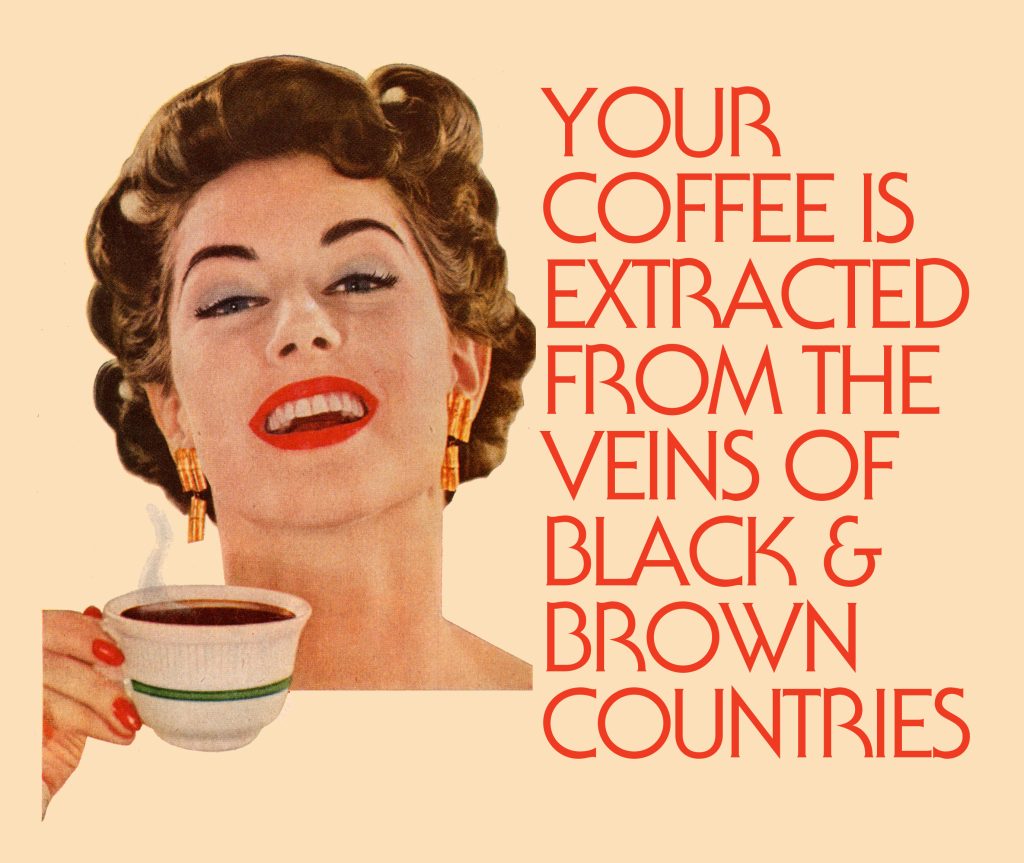

Coffee is a $430 billion dollar industry amassed off the labor of Black and Brown people. Yet, African countries—where the plant has always grown or was forced to grow due to colonialism—make almost two percent of that money cumulatively. While the industry has increasingly tried to re-think its practices, particularly where sustainability is concerned, it has yet to reconcile the history of violence, theft and slavery that built one of the most consumed beverages in the world. On a mission to rectify this is the Memphis, Tennessee-based brand Cxffeeblack.

Founded by Bartholomew Jones and Memphis’ first Black woman roaster, Renata Henderson (who is also Jones’ wife), Cxffeeblack is a community-oriented and education-based coffee company whose beans are sourced through an all-Black supply chain. Each brew—from the fruit-forward and complex Guji Mane to the buttery Black on Both Sides—works to reclaim and amplify the Black history behind coffee.

“Most research says that coffee was discovered somewhere in the southern region of Ethiopia around 850 BC,” Jones tells COOL HUNTING. “That region of the world was where the first Arabica trees [the species that grows coffee] were discovered and cultivated. In the Guji zone in particular, where we source our coffee, they have really old, beautiful rituals and traditions.”

“One, for instance, is Buna Qalaa,” he continues. “If you think about it, that’s the world’s first bulletproof coffee because they will roast the coffee seeds and cherry with butter from the cows that they herded; they were pastoralists. The reason why they did that ceremony, Buna Qalaa, is because they wanted to preserve life. People think about environmentalism and sustainability as a new thing, but in reality Indigenous communities across the world have always been sustainable. So one of the things that they did was instead of sacrificing animals, they slaughtered coffee. ‘Qalaa’ means ‘slaughter’ and ‘buna’ means ‘coffee.’ Because of that there was a blessing that came to be associated. They saw coffee as the seeds of peace; the word for peace in Afan Oromo—which is the language that the people there speak— is ‘nagayaa.’ So the blessing, ‘Buna fi Nagaa hin Dhabiinaa,’ means ‘May your house lack no coffee nor peace.'”

Despite these rich origins in Ethiopia, those who began the ancient traditions and age-old cultivation processes scarcely see any of the profits or recognition for the brew. This invisibility is colonialism at work, as early Europeans stole the plant from where it was indigenously grown and exported it around the world—from Vietnam to Haiti and Brazil—where they forced individuals, namely West African people who were enslaved, to farm it.

Today, this history is nowhere to be found in typical coffee shops. In fact, the inverse feels true; the arrival of a Starbucks location or other coffee shops signifies gentrification or a white community (or both), further alienating the drink from its origins.

“I was going to coffee shops and started to see some dissonance,” says Jones. “I’m going to the shops, I’m seeing these coffees from different melanated countries, but I’m not really seeing any melanated people here. Why is that?” This observation is central to the ethos of Cxffeeblack, which is why they operate out of the Memphis shop, called Anti-Gentrification Coffee Club, located in a predominantly Black neighborhood in the city.

Y’all pay all this care and attention to the scales or to the weight, to the pitchers, to the bloom time, to the refractometer and all these things, but there’s no care for the people who produce this

“Coffee comes from the same place we come from. Y’all pay all this care and attention to the scales or to the weight, to the pitchers, to the bloom time, to the refractometer and all these things, but there’s no care for the people who produce this,” explains Jones. “We believe that we will be able to reintroduce coffee into our communities and sell coffee from an all-Black supply chain to the world. Then, we’ll be able to redistribute the wealth from the profits in that coffee back into Black communities globally to help redistribute a lot of the wealth that was taken from our ancestors.”

Cxffeeblack sources their beans from farms they’ve visited in Ethiopia where it’s also processed and checked for quality by a community leader. From there, it’s taken to a Black-owned exporting company, checked again for quality and shipped to a Black-owned importing company based in the US. When it finally arrives in Tennessee, it’s roasted by Henderson.

“She is the roaster because in Ethiopia traditionally coffee, coffee-roasting and being a barista has been a part of Black womanhood for 2,000 years. So we wanted to continue that and share that perspective, which unfortunately is very rare,” Jones says. “When you think about a roaster or a barista, a Black woman is the last person that comes to mind even though they certainly were the first ones to do it. So we wanted to honor that; my wife was able to go over there and learn traditional roasting.”

While thoughtful intentions to the community and ancestry permeate everything Jones and Henderson do (including their recent release, a coffee called Woman King which is grown by a women’s collective in Congo), their coffee’s quality also stands on its own, bolstered by the duo’s years of experience in the industry. The Guji in a Can, a Snapchilled version of their original Guji offering, is the perfect example. Using Snapchill’s proprietary technology, which brews coffee hot and then instantly freezes it to 34 degrees to prevent oxidation (a strategy in vein of the Japanese flash chill), Cxffeeblack’s cold coffee alternative preserves the beans’ plurality of flavors in a way that even cold brew purists will find convincing.

From their onset in 2019, Cxffeeblack has always been more than a coffee company; it’s a multidisciplinary organization helping their community learn and connect to the forgotten ancestral roots of coffee. Right now, they are working on an upcoming HBO Max series that is based on Jones’ life and which he describes as “based on a rapper who becomes a teacher and then loses his job and has to start a coffee shop in the hood to stop it from being gentrified.” He tells us, “We’re going to be able to address some really important issues, but in a palatable way. The first episode addresses the shop getting broken into, which is what happened to us, and addresses police brutality.”

They also recently released a documentary about coffee and a pair of sneakers, the pan African CXFFEEBLACK runners, in order to fundraise for a Black barista exchange program. “The goal is to use the proceeds to be able to bring four baristas from Africa and then four baristas from the community that we partner with and just brainstorm, share education, do a co-op, swap information and ideas about how to like bring it closer to our communities,” says Jones.

“I want to see our community really integrating coffee in a way that’s contextual, not just do a Black version,” he concludes. “To be honest, to me, it’s hip-hop; it’s a sample. It’s sampling the roots of our past, chopping it up and conceptualizing it in our present and then using that as a bed for imagining a better future for our community globally.” With Cxffeeblack, Jones and Henderson work toward decolonizing coffee and the world at large.

Images courtesy of Cxffeeblack