Interview: David Shrigley on his Whimsical Collaboration with Maison Ruinart

From a series of eccentric illustrations to an “unconventional” online gallery, a partnership of profound joy

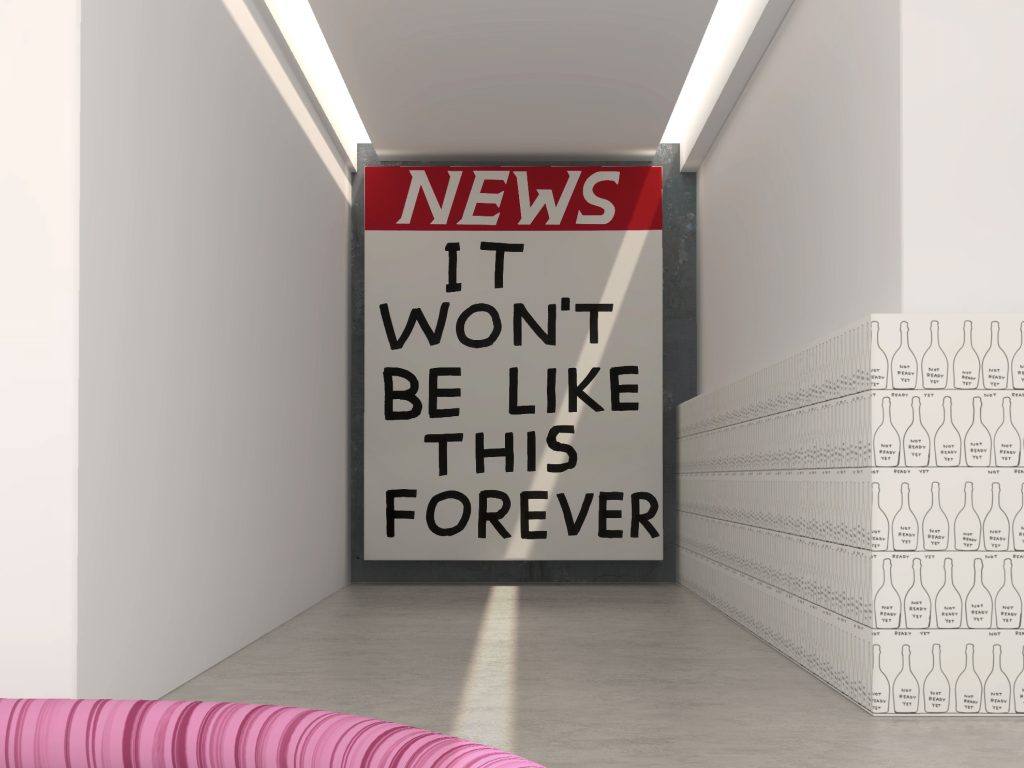

During Art Basel Miami Beach 2021, official Champagne partner Maison Ruinart once again unveiled a partnership with a contemporary artist of exceptional merit. This year, it was beloved multi-disciplinary artist David Shrigley who interpreted the luxury brand’s effervescence and the pristine process behind its production. Shrigley first partnered with Ruinart in 2020, but this year saw his witty, wise and wondrous large-scale works appear in the fair’s collectors lounge, amidst an outdoor event at the Miami Beach Botanical Garden, as part of an Acute Art augmented reality installation at The Bass museum and through The Unconventional Gallery, which everyone can access online. Shrigley’s magical imagination couples well with the luscious liquid—so we sat down with the artist to learn more about his signature style, interests outside of art and how he ideates.

First, are you aware of the joy your art brings people?

I don’t think one ever has a sense of how other people see them or their work.

Art that utilizes words can sometimes be tedious or far too self-serious. But there’s a playfulness or silliness to your work that makes it pleasurable and poetic. Do you see yourself as a poet? Or do you identify as writer as much as an artist?

I do not see myself as a writer. I always feel inept as a writer, though I enjoy books and reading. The writers I like, I feel in awe of them. I feel like I might be able to write a good sentence whereas they can write a good book. I couldn’t possibly do that. To write something, even the foreword to a book, I’m always like, “I can’t do that.”

Words are really important, though, and I use them in a certain way. I’ve published a book of poetry—not that it’s really seen the light of day. I wrote it on long-haul flights maybe 10 years ago. The book is called Long Haul. It could be hard to track down. The premise was that I would sit on two round trips between San Francisco and Glasgow, where I lived at the time, and I would write a book of poetry in the 40 hours of flying time. It was basically about how bored I was on the plane because I didn’t have my drawing equipment with me.

I’ve done other projects where I’ve written lyrics. I’ve done that quite a bit over the years—written lyrics that other people have interpreted, and worked with musicians. More recently, I’ve started to write songs myself. Since I turned 50, I figured it was OK to pick up a guitar again because nobody was going to judge me. That’s my literary output.

That wit and wisdom that underscores the written part of your art—do you feel an electricity when you’ve got something really good?

No. Not at all. For me, the work is the residue of the process. That’s the way I approach it. That’s also the way to diminish the anxiety you might have about it. All you have to do is make the work. Really, the work makes itself. As long as you get up in the morning and go to the studio, the work will make itself. You just pursue it.

How does that residue transform into what we see in gallery shows?

Well, you have all this stuff—drawings, mostly graphics on paper in my case. You might also have 100 paintings. What used to happen until about five years ago, of those 500 drawings and paintings, I would select maybe 30 and send those to the gallery and say, “This is the exhibition.” When going through my accounts, I would look at the inventory of what was sold but never closely.

One time, maybe five years ago, I was doing a survey show and they wanted some original works on paper so I asked for the PDF of all the works still at the gallery. I looked at the thumbnails of all this unsold work and I said, “Nobody bought that” and “nobody bought that” and “nobody bought that!” I asked, “What did they buy?” It was the pictures of cats. It was all of the works that I thought were substandard and I almost threw away but held onto. That’s when I realized that this part is the commercial activity. Obviously it is art when I am doing it in the studio, but what happens after is a commercial activity.

What about your online presence?

We have the great aggregator which is Instagram, where suddenly you’re like, “I am going to post this one of a cat” and it gets 100,000 likes. I get given the works for Instagram by my assistant who reformats them for the platform and I post them every day. I get sent 100 at a time, and when I get to the last 15 I’m like, “Oh these are the crap ones” and of course you post the one you think is crap 100,000 people like it. But the first one you posted, the one you thought was genius, nobody liked it.

Do you derive from your artistic process? Is there something outside of art, as well?

I’d say that being in the studio, making the work is a very joyful privilege. I’m very immersed in my work and I kind of have to be. Even though I want a work-life balance, the work brings me great joy. It’s like a therapy as well. At the same time, you need to switch off and do something else. Since lockdown, walking to the top of the hill with my dog and looking out at the ocean around the village where we live in Devon always makes me happy. I think it makes the dog happy too.

I’m also a big football fan and I like contemporary music. I listen to music when I’m not writing any words. When I’m just making pictures of things I do listen. When it’s time to start making words, I turn it off. I have fairly eclectic taste but indie-rock is my thing. I’ve always loved live music. I’ve started to go see soccer games again. I’ve loved it since I was a little kid. It was one of those things that became really uncool when I got to art school in the late 1980s. I was totally obsessed but I felt like I had to not talk about it.

There was a weird thing that happened in the early ’90s where it became cool—and cool to talk about—and I found that nauseating. For me, it was about a deep emotional connection. It wasn’t cool! It was like saying being in love is cool. It’s not. It’s just a thing. It’s like torture. It’s either abject misery or ecstasy. That’s the relationship you have with your team.

How did this partnership with Maison Ruinart come to be—and what made you take it on?

In 2019, I was approached by Ruinart. Increasingly, I don’t do a lot of collaborations with brands though I have done a lot over the years. The criteria has always had to be that I do something where I learn. After a certain point, you don’t haven’t anything to make art about if you do not do stuff kind of like this, where you deliberately go down a different path.

If I hadn’t done this project I would have never gone to Reims, or visited the caves. I would have never had insight into the production of something I really like. I really like wine, and particularly French wine. There’s that relationship to the soil that’s particular to France. French wine is named after the soil, the region—rather than the grape.

Can you talk about your ideation process and how you came to the words and images?

When I first started visiting Reims, I was gathering information. I had a tour. I visited the archive. I spoke to the archivist and the cellar master. I spoke to people in the vineyards, and then the marketing people. I was interested in writing a list of all the things they wanted to say about their brand. Obviously I’m not making an advert. I am not in marketing. I just enjoyed re-delivering these messages in my own way—wondering what would be acceptable and what wouldn’t.

I ended up with these statements about worms working harder than us. I am quite proud of that because I arrived at this statement, which is sort of nonsensical and implies different things, I realized it is like advertising from a parallel universe. It’s also a sincere statement. The soil is really important and the aeration and the nutrients of the soil are important on a scientific level. Soil is a misunderstood resource.

Hero image courtesy of Happy Monday